Months after the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a proposal to roll back net neutrality policies enacted in 2015 under President Barack Obama, the Commission today formally repealed rules that prevented internet service providers (ISPs) from discriminating against certain apps and websites.

Today’s implementation of the “Restoring Internet Freedom” order, led by Republican Chairman Ajit Pai, is a hot-button issue.

In December 2017, 22 million comments were filed on the commission’s online public forum. In February, a coalition of companies and 23 state attorneys general challenged the rollback in court, alleging that it violated the Administrative Procedures Act and Communications Act of 1934. And some states took matters into their own hands: In March, Washington State passed a bill into law prohibiting telecom providers from blocking content and throttling traffic, and in May, the California State Senate followed suit. (More than two dozen other states, including Maryland, Connecticut, and New York, are considering net neutrality legislation of their own.)

So why is today’s net neutrality decision so controversial? Here’s what you need to know.

What is net neutrality?

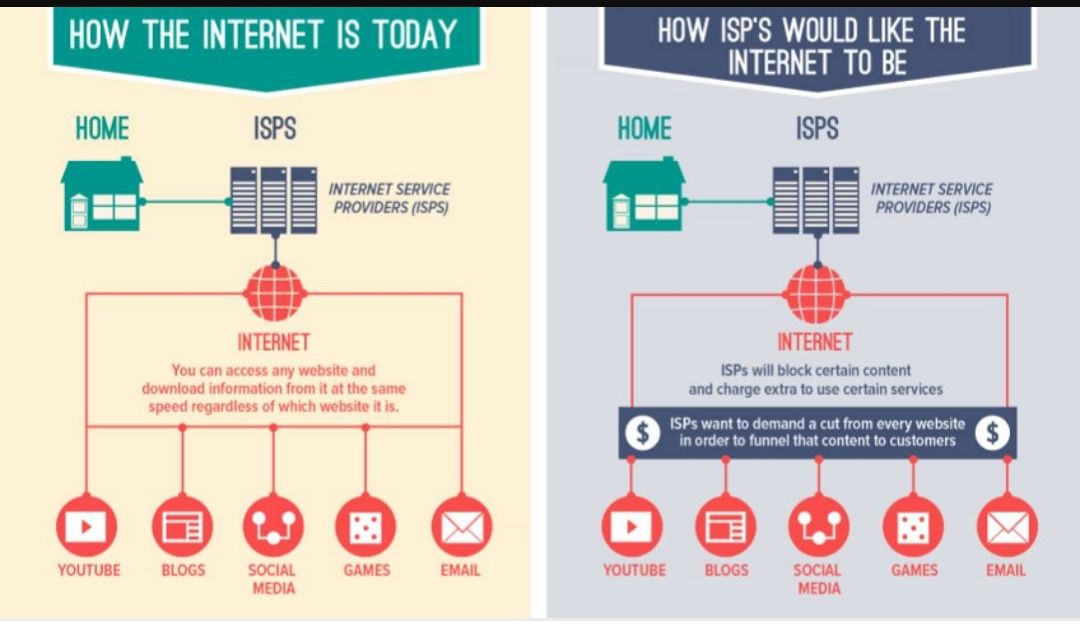

The term “net neutrality,” which was coined by Columbia University media professor Tim Wu in 2003, is the principle that all internet traffic should be treated as equal, regardless of the source of the traffic. A truly “neutral” ISP doesn’t block or slow down an app, service, platform, or user for any reason, so long as they’re engaged in legal activities. Just as importantly, it doesn’t charge extra money for prioritized traffic to certain websites or applications, or offer “fast lane” access to first-party services without extending the same courtesy to its competitors.

A widely cited violation of net neutrality principles is Comcast’s throttling of peer-to-peer (P2P) applications such as BitTorrent. In 2007, an investigation by the Associated Press found that the ISP intentionally slowed down the upload speeds of certain apps, and continued to do so until the FCC ordered it to stop.

Cellular carriers have run afoul of net neutrality rules, too. In 2012 and 2013, AT&T limited access to Apple’s FaceTime and Google Hangouts on certain data plans. At the time, it said it would only “enable” FaceTime on its cellular network for customers who upgraded to a subscription without unlimited data.

Which net neutrality rules were repealed?

The FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order — spearheaded by then-chairman Tom Wheeler — reclassified broadband internet service under Title II of the Communications Act. It grouped ISPs, which were formerly considered “information services” in the eyes of the law, with landline phones, electricity, and utilities as “common carriers.” The Commission didn’t apply the full weight of Title II to cable companies and wireless carriers — it used a process called “forbearance” to selectively choose which sections to enforce — but it established certain rules to which ISPs were required to adhere.

Specifically, ISPs couldn’t block content or throttle internet speeds unreasonably, or create “fast lanes” for certain services that disadvantaged others. It also subjected cellphones, tablets, and other mobile devices to the same rules as landline devices, and explicitly banned “paid prioritization,” the practice of charging services, apps, or websites a premium for high-speed access to customers.

The Restoring Internet Freedom Act throws many of those rules out the window. It effectively narrows the FCC’s definition of a net neutrality violation to instances of non-disclosure. ISPs are free to slow down or block websites so long as they’re transparent about those practices with subscribers.

The FCC won’t challenge ISP policies. It will instead defer to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) on issues of broadband regulation, which will now be responsible for ISPs that violate subscribers’ contracts or participate in anticompetitive activities.

“The bottom line is that our regulatory framework will both protect the free and open internet and deliver more digital opportunity to more Americans,” Ajit Pai wrote in an op-ed. “It’s worked before and it will work again. Our goal is simple: better, faster, cheaper internet access for American consumers who are in control of their own online experience.”

What does it mean for me?

The repeal of the FCC’s blocking, throttling, and prioritization rules won’t result in changes today, this week, or even this month. But they open the door to pricier data plans and slower service from ISPs.

An ISP such as Comcast could, for example, charge social networks like Facebook and Twitter; streaming services like Spotify, Netflix, and YouTube; and search engines like Google, fees for faster connections to subscribers. Consumer advocacy groups have expressed fears that ISPs will sell subscription bundles of websites (e.g., a “social media” or “streaming video” bundle) akin to cable packages, which might lead to the emergence of lower-priced plans with access to only a small selection of websites. But ISPs will likely to try to pressure customers into higher tiers by throttling speeds and imposing strict data caps.

Internet providers including AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast have said they won’t slow down or block content. But if the worst comes to pass, it could sound a death knell for startups who don’t have the cash to compete with incumbents.

“Cable and phone companies won’t start misbehaving right away, because they know they’re being watched,” Evan Greer, deputy director of digital rights group Fight for the Future, said in a statement. “But over time, unless net neutrality is restored, the internet as we know it will wither and die.”

Some ISPs have an incentive to put competitors at a disadvantage. Comcast, for example, launched a streaming television product in 2015, Stream TV, that competes against over-the-top TV services like Sony’s PlayStation Vue and Dish Network’s SlingTV. Stream TV doesn’t count against subscribers’ data caps, and nothing precludes Comcast from charging Dish Network or Sony for the privilege. Costs from payments extracted by ISPs will inevitably be passed along to subscribers.

Companies that don’t cough up fees risk being blocked entirely. In 2013, Verizon told a federal judge that it had the right to prevent users from accessing websites and services if those websites and services didn’t pay.

Some ISPs and carriers have adopted a policy of “zero-rating,” offering “free” data for apps like Netflix and Apple Music (T-Mobile’s Binge On is perhaps the best example of this), which were legal under the FCC’s freshly jettisoned net neutrality rules. But now, there’s nothing to prevent carriers like Verizon and AT&T from reintroducing “sponsored data” programs that discriminate against competitors. (Former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler issued a report in January stating that AT&T’s Sponsored Data and Verizon’s Go90 programs violate the Open Internet Order.)

Another unfortunate effect of today’s rollback? If you suffer wrongdoing at the hands of an ISP, it could be a while before your complaint is adjudicated. The FTC oversees consumer protection and competition, but only after the fact. Investigations can take years, and because it lacks the FCC’s rule-making authority, it can extract only voluntary commitments from companies. It canenforce antitrust issues, but those have to meet a higher legal standard.

Are there efforts to reinstate net neutrality?

Efforts are underway to reinstate net neutrality principles at the state level, but they’re up against a legal roadblock; the FCC’s new rules explicitly ban states from adopting their own net neutrality laws.

In states like New York and Montana, governors have signed executive orders banning local government from doing business with ISPs that don’t agree to net neutrality principles.

Congress, meanwhile, faces challenges of its own.

In May, the Senate passed the Congressional Review Act, which would give Congress 60 legislative days to undo regulations imposed by a federal agency. However, a companion bill in the House, which has a larger Republican majority, looks unlikely to garner the necessary votes. And in any case, it would need to be signed by President Donald Trump — an unlikely prospect, given that Pai is one of his appointees.

Short of a permanent solution from Congressional lawmakers, the best chance at restoring net neutrality principles is electing a pro-net neutrality President in 2020 who selects pro-net neutrality FCC commissioners.

What do you think about Net Nuetrality? Do you agree woth neing regulated or non-regulated? If you would like to comment on this article or anything else you have seen on my feed Please share your thoughts in the comment area below.